Few tools have earned as much reverence in professional kitchens as the Japanese knife. Born from centuries of swordsmithing tradition, these blades represent a fundamentally different philosophy to their Western counterparts; one that prioritises precision over brute force, and encourages cooks to work with ingredients rather than simply against them. For anyone serious about cooking, understanding the main Japanese knife types (and crucially, when to reach for each) is a skill worth developing.

The distinctions matter because Japanese knives are designed for specific tasks in a way that Western all-rounders simply aren’t. A yanagiba exists for one purpose: to slice raw fish in a single, uninterrupted stroke that preserves cellular integrity and maximises texture. A deba’s heft is engineered to break down whole fish without the kind of blade damage you’d inflict on a thinner knife. This specificity can seem intimidating at first, but once you understand the logic behind each blade, building a collection becomes almost intuitive.

The Everyday Workhorses

For Slicing Meat, Dicing Onions & Mincing Herbs: The Gyuto

The gyuto is where most cooks should start. Translating literally as ‘cow sword’, it emerged during the Meiji era as Japan’s answer to the Western chef’s knife, though with a distinctly Japanese interpretation.

Gyutos are thinner, lighter and harder than their European equivalents, making them exemplary Japanese kitchen knives that accommodate both the rocking motion familiar to Western cooks and the push-cutting technique favoured in Japanese kitchens.

For home cooks, a 210mm blade offers the ideal balance of reach and manoeuvrability; professionals typically opt for 240mm or longer.

For Dicing, Slicing & Chopping On Smaller Boards: The Santoku

The santoku occupies similar territory but with a different personality. Its name means ‘three virtues’ (referring to meat, fish and vegetables) and its shorter, flatter blade with a sheepsfoot tip makes it particularly nimble on smaller cutting boards. Where the gyuto encourages a slight rock, the santoku excels with a straight up-and-down chopping motion.

Many home cooks find it more approachable than a gyuto, and its typical length of 165 to 180mm suits compact kitchens perfectly.

For Dicing & Slicing With Added Tip Precision: The Bunka

The bunka deserves mention here too. A hybrid that combines elements of both the gyuto and santoku, it features a distinctive pointed ‘k-tip’ that adds precision for detail work whilst retaining the versatility of an all-purpose blade. Think of it as a santoku with slightly more attitude.

Read: How to land your first job in a professional kitchen

Vegetable Specialists

For Chopping Vegetables: The Nakiri

Japanese cuisine places enormous emphasis on vegetable preparation, and two knives have evolved specifically for this purpose.

The nakiri is the more accessible of the two: a thin, rectangular double-bevel blade designed to make full contact with the cutting board on every stroke. This eliminates the accordion cuts that plague curved blades and makes quick work of everything from leafy greens to dense root vegetables. Its tall blade also doubles as a handy scoop for transferring ingredients from board to pan.

For Paper-Thin Cuts & Decorative Garnishes: The Usuba

The usuba is the nakiri’s professional-grade sibling, distinguished by its single-bevel edge. That single bevel allows for extraordinary precision (essential for techniques like katsuramuki, where a daikon is peeled into a continuous paper-thin sheet) but demands considerably more skill to use and maintain. Unless you’re planning to pursue traditional Japanese cooking seriously, the nakiri will serve you better.

Fish & Butchery Blades

For Slicing Sashimi: The Yanagiba

This is where Japanese knife design truly diverges from Western tradition. The yanagiba (sometimes called shobu, meaning ‘iris leaf’) is the archetypal sashimi knife: long, slender and single-bevelled. Its purpose is to slice boneless fish fillets in one fluid drawing motion from heel to tip. This single-stroke technique minimises cellular damage, which is why sashimi sliced with a yanagiba tastes fresher and has better texture than fish hacked with an inappropriate blade.

Lengths range from 240mm for home use up to 330mm or longer for professionals working with whole sides of tuna.

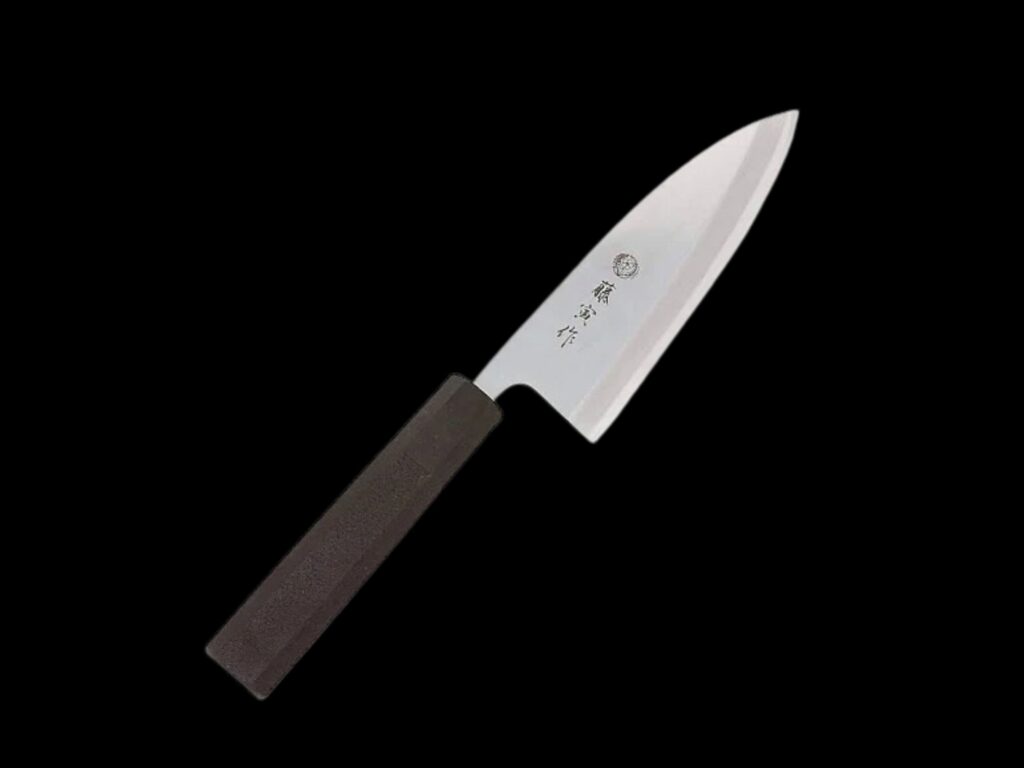

For Filleting & Breaking Down Whole Fish: The Deba

The deba handles the heavier work of fish butchery. Thick, heavy and robust, it’s built to break down whole fish: splitting heads, cutting through pin bones and separating fillets. The spine is sturdy enough to crack through small bones (using a gentle tap from your palm rather than forcing the blade), whilst the pointed tip can navigate around joints with surprising delicacy.

A 165mm deba suits most home fish work; professionals handling larger specimens typically reach for 210mm.

For Deboning Chicken & Poultry: The Honesuki

For meat, the honesuki is the Japanese answer to a boning knife, though with a crucial difference. Where Western boning knives are flexible, the honesuki is rigid and triangular, designed for precision work around poultry joints rather than the sweep-and-flex technique common in European butchery. Its stiff spine provides the leverage needed to pop through cartilage and separate joints cleanly. The garasuki is essentially a larger, heavier version built for butchering bigger birds or more demanding tasks.

The Precision Tools

For Peeling, Trimming & Deveining: The Petty

Every kitchen needs a small knife for detail work, and the petty fills that role beautifully. Essentially a scaled-down gyuto (typically 120 to 150mm), it handles everything from peeling and trimming to breaking down small ingredients that would feel awkward under a full-sized blade. Many chefs consider it as essential as their main knife.

For Carving Roasts & Slicing Cured Meats: The Sujihiki

The sujihiki is Japan’s slicing knife: long, narrow and double-bevelled. Unlike the yanagiba (which is purpose-built for raw fish), the sujihiki excels at carving roast meat, slicing smoked salmon or breaking down any boneless protein where clean, even cuts matter. Its narrow profile reduces drag and friction, allowing the blade to glide through flesh without tearing. Think of it as a more refined, harder-edged alternative to a Western carving knife.

Understanding Japanese Steel

Japanese knives perform differently to Western blades largely because of their steel. Traditional high-carbon steels like shirogami (white steel) and aogami (blue steel) can achieve extraordinary hardness and take an exceptionally keen edge, though they require more maintenance as they’re prone to rust and patina.

White steel is prized for its purity and ease of sharpening; blue steel adds tungsten and chromium for improved edge retention and slightly better corrosion resistance.

Stainless options like VG-10 and AUS-10 offer a practical middle ground: sharp, reasonably hard and far more forgiving of occasional neglect. For most home cooks, a quality stainless Japanese knife represents the ideal balance between performance and low maintenance.

More exotic powder steels like SG2 and ZDP-189 push hardness and edge retention further still, but at a price premium that’s harder to justify outside professional settings.

The Bottom Line

Start with a gyuto or santoku as your primary blade, add a petty for detail work, then expand based on how you actually cook. If you prepare a lot of vegetables, a nakiri earns its drawer space quickly. If you’re buying whole fish, a deba becomes essential.

The beauty of Japanese knives lies in their specificity; each blade does one thing exceptionally well, and building a collection means gradually assembling the right tool for every task your cooking demands.