The morning after Bruce Springsteen played San Sebastián, in a show that lasted well into today, we took the bus west along the Basque coast. Forty minutes of winding road, hungover, dehydrated from too many gildas back in Donostia, the Bay of Biscay glittering to my right through salt-smeared windows, taunting me. The night before had been The Boss. Today would be The King of the Sea.

An afternoon of excess fish isn’t always what you need after a big night on the Bruce and beers, with a lurching, sticky hot bus journey just to really shake the stomach up – the final indignity. But as we turned the corner into Getaria and the views of the bay opened up, things settled considerably.

Getaria is a medieval fishing village of perhaps 2,500 people, built on a tombolo connecting the mainland to Monte San Antón. The locals call that hump of land El Ratón – the Mouse – for its rodent-like silhouette. Surrounding it all are the steeply terraced vineyards of the Getariako Txakolina DO, the most prestigious appellation for txakoli, the region’s white wine.

The village also claims three famous sons: Juan Sebastián Elcano, the first man to circumnavigate the globe, completing the voyage after Magellan died in the Philippines in 1521; Cristóbal Balenciaga, the fashion designer Coco Chanel called the only true couturier; and Aitor Arregui, a former professional footballer who now runs one of the most celebrated seafood restaurants on the planet.

So, we arrived kitted out head to toe in Balenciaga, hungry for more than Elcano’s lucrative cargo of cloves and cinnamon. It’s fish we’re after, grilled by the son who stayed.

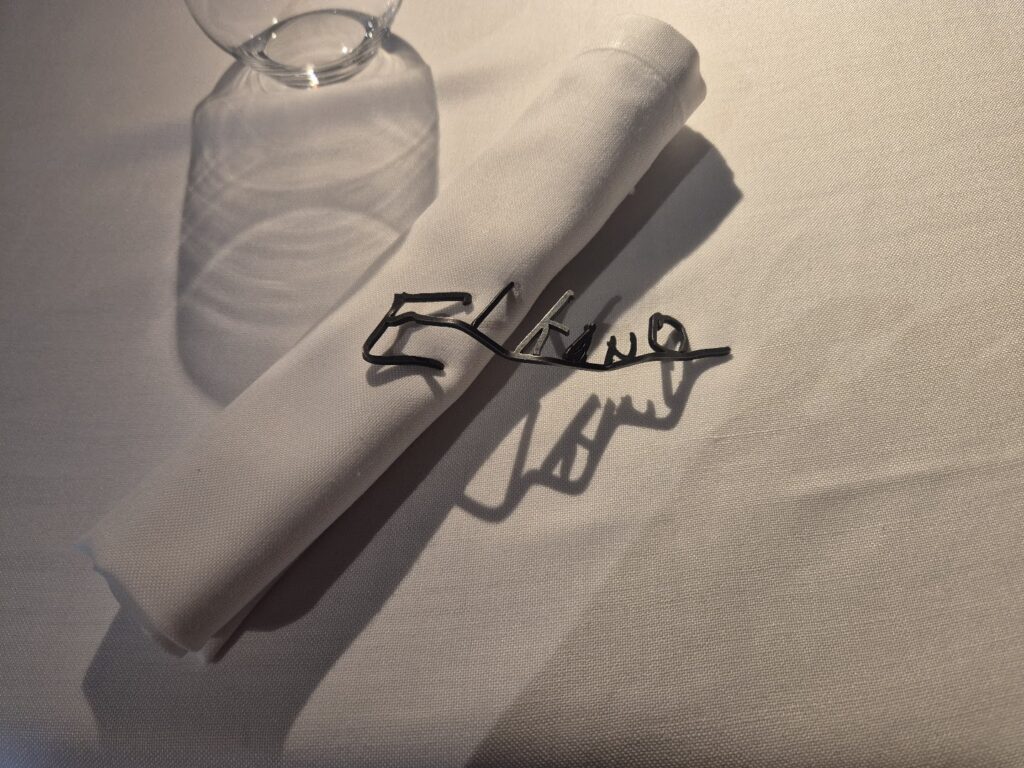

Elkano sits on Herrerieta Kalea, a few minutes’ walk uphill from the harbour, a minute down from the bus stop. The building’s curved white facade has the profile of a ship’s prow, facing out to sea – appropriate for a place whose whole philosophy rests on its proximity to the water. The restaurant takes its name from the explorer, opening in 1964 when Aitor’s father Pedro Arregui returned from two years working abroad and transformed his mother’s grocery store into a bar, installing a street-side grill beside it.

It felt like a natural thing to do. Fishermen here have long grilled their surplus on boat-mounted setups, and legend has it that Elcano himself left grills from his second circumnavigation as inheritance to his descendants. When Pedro opened the restaurant, the idea was simple, democratic, even: neighbours could come in after returning from the boats and cook their own catch over the coals.

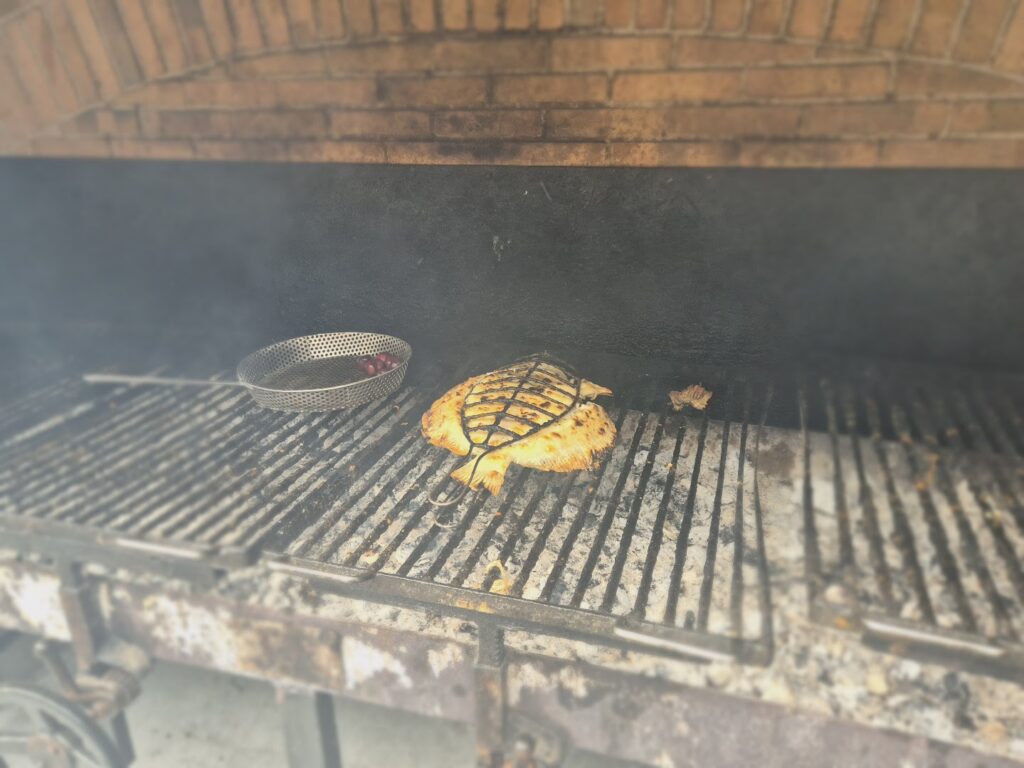

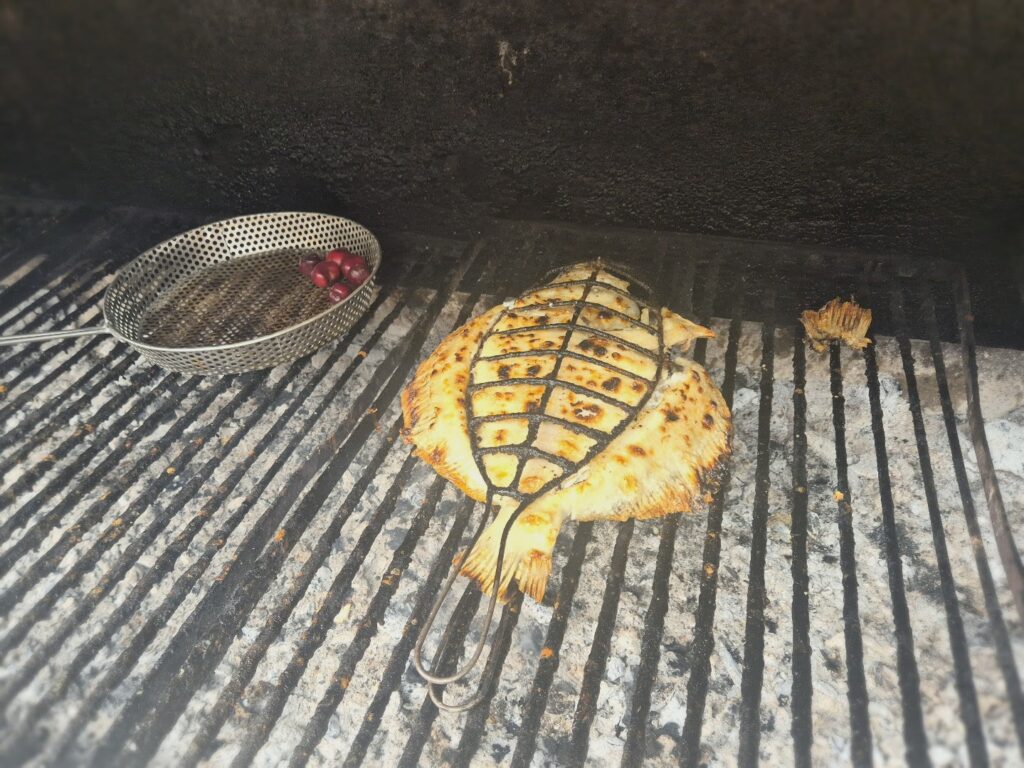

Then he started experimenting, grilling hake heads, a cut traditionally used to bolster soup, and kokotxas, the gelatinous throat cheeks now prized across the Basque Country. And when a fisherman brought him a particularly large turbot, Pedro decided to grill it whole, skin on – a departure from local custom, where only the ‘noble’ loins were served as fillets and the rest consigned to the stock pot. Cooking it whole, skin intact, trapped the fish’s abundant gelatin, keeping the flesh rich and succulent. It also unlocked the inherent beauty of the fish’s lesser cuts: the cheeks, the collar, the sticky wings – parts that had previously been discarded.

This became the dish that would make Elkano famous: whole grilled turbot, cooked over holm oak charcoal and seasoned with nothing more than coarse salt and spritzes of a mixture of oil and vinegar that the family calls ‘Agua de Lourdes’. The recipe remains an almost mythical secret. When asked about it, Pedro would just smile and look at his wife.

The Arregui family philosophy rests on three principles: proximity, product knowledge, and restraint. Be near the fish, understand its life cycle, don’t ruin it. Pedro used to say you should look a fish in the eyes to check for brightness; if they still shine, it’s truly fresh. If it blinks, throw it back (he didn’t say that).

Today, fishermen and farmers bring their catch and produce directly to the restaurant, as they have for six decades. Some of the suppliers are the sons of men who sold fish to Pedro in the 1960s. Fishing in Getaria, like grilling, is generational. The grill is still available to locals. There is just one stipulation: the fish must be worthy.

Pedro died in February 2014, aged 73. That November, Elkano was awarded its first Michelin star. The timing was bittersweet, although one suspects this thing isn’t concerned with stars at all. By then, his son Aitor had long since returned to the kitchen. He’d “distracted himself” for a decade as a professional footballer – playing in La Liga for Alavés and Villarreal – but was back by 2002, Elkano’s gravitational pull stronger than the tides. Now he runs the place with the cool authority of someone who has inherited both a business and a way of seeing the world.

The Meal

We arrived early afternoon, the sun still high over the harbour. Outside, the grills were already loaded – whole turbots blistering in the open air for diners who hadn’t even ordered yet. Through the dining room, where a large family was mid-way through a long lunch – bones piled on platters, bread crumbs scattered across the tablecloth, the happy carnage of a long meal – we climbed the stairs to the first floor. No harbour views from up here, but you’re close enough to smell the salt.

Upstairs is another register entirely. Grey walls, wooden beams, white tablecloths. A doll on a shelf – some maternal figure, perhaps. A sprig of dried sea grass in a cork stand on our table, a QR code on a wooden block for the menu, nothing else. Whether this was in the name of sustainability – always good posture for a fish restaurant – or a stylistic choice to keep the table stark, we never found out.

The space is austere, almost monastic, but this isn’t a dining room of hushed tones and genuflection. Downstairs, the family were still at it, volume rising. Around us, chatter and the clatter of cutlery. In such a revered restaurant, noise is a relief.

The menu opens with a statement of intent: “We are in Getaria, the southernmost tip of the Bay of Biscay. Latitude 43°, 2′. Today, just like every day, the arrantzales went out to sea and brought us the best our coast has to offer… This menu is the best of today, here and now. Full speed ahead.”

Full speed ahead, indeed; I was hungry.

First came a light seafood broth, golden and delicate. So ethereal, in fact, that it dissolved in my memory the moment it’d been eaten, and I can’t remember a thing about it despite photo evidence.

Then two cubes of raw mackerel, cold, clean and bright, a single strand of pickled pink onion balanced across the skin’s silver sheen. Marinated lobster with its roe followed, the flesh taut and squeaky, pops of salinity punctuating naturally sweet, robust protein. A flood of acidity from the tiniest dose of fresh tomato cleansed the palate. The meal was escalating, each course shedding delicacy, gaining heft, preparing the ground for the grill.

Now things were moving. Kokotxas (hake throats) in a trio of different preparations, representing three generations of the family: grilled, fried, and pil-pil. Its plate was pure white, almost disappearing into the linen beneath it – exposing the nakedness of the dish, but the trio was fully-flavoured and tasted boldly of the sea. If the Cantabrian had been cut with gelatin and steeped in garlic, that is.

Then spring mushrooms, ceps and trompettes, meaty and kissed with the smoke of the holm oak coals, as though the kitchen sensed it was time to get substantial.

What strikes you, eating at Elkano, is the near-total absence of vegetables. There is no garnish, no side of greens, no roasted accompaniments – the mushrooms an exception that proves the rule. The effect is almost austere. But it also highlights something profound about the place: in a fishing village where boats return each morning loaded with the day’s catch, fish is the thing that can be served generously, without restraint. Vegetables are the import, the luxury. Here, a whole turbot for two is not extravagance. It’s simply what abundance looks like when the sea is your garden.

Baby squid (chipirón) next, charred in places, tender and mi-cuit in others, the mantle, fins, and tentacles dissected across a slick of squid ink, each with different tension and give. A quenelle of relish that looked bruising turned out mellow and sweet.

And then the grouper.

Turbot gets the press at Elkano, the magazine features and chef pilgrimages. But the restaurant’s philosophy is about whatever is best that day, whatever the boats brought in. On a sunny day in late June, that was the grouper, one of the finest bits of fish I’ve eaten, a total contradiction. The flesh was impossibly sticky with collagen and actually adhered to the plate, each flake bound together, sturdy and meaty, but somehow also falling apart at the gentlest pressure. The skin wasn’t charred but golden from the grill. No sauce. No accompaniment. Just fire, salt, and the Gulf of Biscay. You got two thick cubes each, the idea of a ‘tasting’ menu seemingly falling away in favour of something more generous.

Smoke was becoming more apparent with each course now. Giddy from the grouper, we threw caution into the sea breeze and added a supplementary gratinated spider crab, served cracked open to reveal bronzed and blistered brown crab meat over a base of softened onions, the shell blackened at the edges from the grill, the innards custardy. You’re given just a dessert spoon, knowingly. It was head-spinningly good.

And then, the turbot. Half a fish for the two of us (we’re not beasts), carried to the table on a platter designed with a lip for collecting the juices. We’d hit the tail end of turbot’s peak window: it’s at its best in late spring and early summer, just before spawning, when the fish fatten on anchovies and oily fish. I’d love to say this was deliberate timing, but…

Aitor himself came to carve, the autopsy an education. If you’ve eaten at Brat in Shoreditch, you’ll recognise the ritual – Tomos Parry’s turbot is an open homage to Elkano. But this is the source. He has an aura, this man: composed, unhurried, deeply present. He wields a fork and spoon in an unusual, studied grip – the spoon turned bowl-upward – using them to anoint each plate with the flesh.

First, the fillets from the underside – the softer flesh that rests against the sand – then the firmer meat from the top, the side that faces the sun. The textures are distinct: one yielding and tender; the other with more resistance, more chew. Then the fins, the meat dragged from the bones with our teeth. The collar, eaten like ribs, collagen smearing our fingers. The neck, placed directly onto my fork, perhaps by my wife, perhaps by Aitor, I think he might have been feeding me, the edges had gone soft. The cheeks, spooned out. The gelatinous wings. Each cut a different proposition, a different ratio of fat to flesh to cartilage, and all of it dressed only with the Agua de Lourdes, which had emulsified with the fish’s own juices into a pil-pil-adjacent sauce. We ate not in reverence but celebration, debris accumulating. The table swinging between hush and clamour until only the bones remained.

Desserts followed: grilled cherries with a cheese ice cream, the freshness of the fruit a reset after relentless unadorned fish, the coals imbuing smoke but meaning too, connecting the course to what had preceded it. Then, a hot hazelnut fondant dusted with salt, pure decadence, a chocolate brownie and coffee ice cream number, more decadence, and cakes and truffles to close things out.

We drank txakoli throughout, Txomin Etxaniz from the surrounding hillsides where the vines climb in every direction, close enough to taste the salt spray. The sea air and Atlantic humidity give the wine its characteristic salinity and bright acidity. It’s poured in the traditional Basque style here, flamboyantly from a height, adding a gentle effervescence. Bone-dry, bracingly acidic, with a faint saline edge – it was the only wine that made sense, grown in the same microclimate as the fish were caught, the terroir of the sea meeting that of the hillside.

The bill was just shy of €500 for two, with the tasting menu at €200 per person plus the spider crab supplement and wine. It is not cheap. But consider what you are paying for: sixty years of accumulated knowledge, three generations of the same family working the same grill, fish that was swimming in the Cantabrian Sea that morning, and a level of restraint that borders on the philosophical.

The World’s 50 Best Restaurants currently ranks Elkano at number 24. It holds one Michelin star and three Soles Repsol. None of this quite captures what the place is. It is not a restaurant chasing modernity or spectacle. It is a family business that has spent six decades learning how to cook fish over fire without ruining it.

Elkano is not trying to show off or impress you, nor is it chasing a fleeting moment of fame. It is trying to show you something true.

We’re heading to Bilbao in search of the city’s best pintxos next. Care to join us?