It’s clear mere moments after setting foot in Bruton that the extravagantly named Merlin Labron-Johnson is an almost mythical figure ’round these parts.

A mononymous presence at hotel receptions, in charity shops and at cafes along the high street, the chef is referenced by folk in the village with a mix of tongue-in-cheek disparagement and genuine admiration.

“Oh, so you’re paying Merlin an arm and a leg only to pick up a kebab on the way home?” would work better as a jibe if there were any kebabys in Bruton.

There are clearly mixed feelings about Bruton’s metamorphosis into every Londoner’s new favourite gastronomic getaway. But however you see it, the chef is bringing footfall to the village; Osip’s second coming has become a meal that people base their whole trip to Bruton, to Somerset, sometimes even the UK, around.

It’s easy to judge other daytrippers, tourists and roving, self-styled ‘foodies’ for doing exactly the same damn thing we’re doing. You see them, wandering around Bruton between meals like zombies, full and confused, listless and hungover, wondering if they can really justify another visit to Hauser and Wirth. It’s a bit of a weird scene quite frankly. Recognising yourself among them only deepens the absurdity of the dance.

Anyway, back to Merlin. The Devon-born (not quite hyper-local in restaurant parlance, but close enough) chef, who won a Michelin star at London’s Portland at just 24, has trained in prestigious kitchens across the continent. But it’s in the Somerset countryside that he’s truly found his home, earning the original Osip its own star in January 2021, less than two years after opening.

Summer 2024 saw Labron-Johnson uproot his vision to more fertile ground—hence the ‘2.0’. Having outgrown its 22-cover space on Bruton’s High Street, Osip now sits a few miles outside town in North Brewham, just about walk-able if it’s not pissing it down and you’re not in heels.

It’s a beautiful spring day when we visit and our shoes are flat, but we take a taxi to the door regardless. Because who wants to rock up to a long meal in a stark white, unforgiving space a little sweaty and a lot dusty? Merlin is namechecked by the driver as we pull up.

Here, sitting pretty at the foot of a pine forest, a 300-year-old former coaching inn (previously known as the Bull Inn) has been transformed into what the chef describes as a true “country auberge”—not merely a restaurant but something that aims at the holistic rural experience reminiscent of the revived farmhouse-restaurants of France.

In doing so, he’s following a model perfected by remote culinary pilgrimages like Sweden’s Fäviken and In De Wulf (where he worked), as well as Kent’s Sportsman closer to home, transforming this corner of Somerset into a bucket list destination for the world’s culinary box tickers. If Bruton’s dedicated Osip signposts didn’t confirm that these goals have already been met, the procession of visitors ambling up Dropping Lane, checking Google Maps every few hundred yards, will do so.

We arrive as a stubbornly gorgeous early evening in spring simply refuses to surrender to dusk, hayfever raging from all the pollen coming off the surrounding fields. There’s a fire pit aflame outside the restaurant serving as a rustic flourish, but it feels a little incongruous in this weather. I wonder if I miss London.

It’s so quiet when we walk in there’s a fear it’s closed, my eruptive sneeze piercing the curated calm of the Osip experience. Quiet, sure, but we’re feeling pretty smug about our early reservation, the dappled light framing rural Somerset at its most captivating.

We begin in the lounge, a nod to the Bull Inn’s former life. It’s an area that could be a country cottage showroom with its obligatory wood burner, the odd scratchy throw, and, curiously, a slight smell of dog. I wonder if they’ve deliberately engineered this aroma, a Heston ‘Sound of the Sea’ kind of vibe. If so, hats off to the commitment to authenticity. If not, bring the good boy out for a stroke.

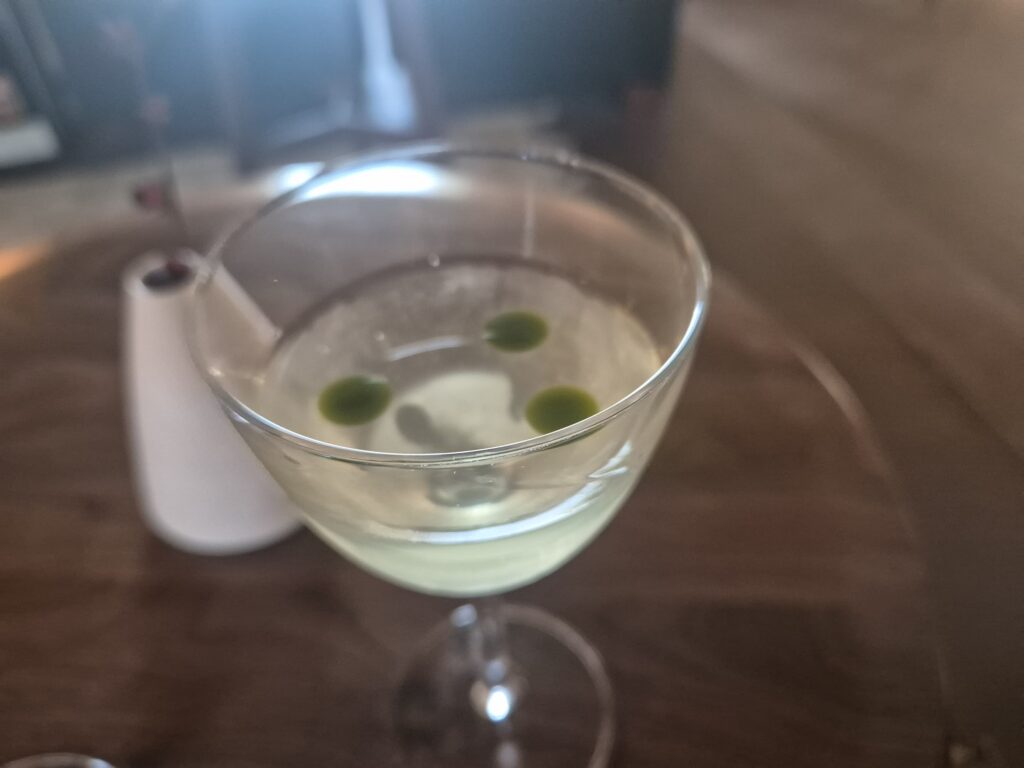

We’re encouraged to kick things off with a cocktail; a preserved tomato martini with little globules of sundried tomato oil that coat the mouth pleasingly with a persistent richness, and a rhubarb sour that was perhaps a little more pedestrian but will certainly wake you up.

A couple of snacks appear on smashed shards of plate that haven’t yet seen the kintsugi treatment. The mushroom and macadamia cookie calls to mind a mini cheddar, and just as delicious. Buried underneath drifts of macadamia is the first of several well judged egg yolks. A pretty-as-petals trout and apple roll – sour forward and with a hint of fattiness from the trout – resets and revitalises.

A reassuring omen; we aren’t instructed in which order to eat these two very contrasting morsels. We luxuriate in the autonomy we’re given – anything to avoid having to hear the conversation of the other couple who are also in this very still lounge, pontificating on the judicious use of quail egg. There’s something about these whitewashed walls that bring about a certain hushed reverence, making eavesdropping unavoidable. We neck our cocktails and loosen up, ready for a new room and the main event.

That restlessness is recognised, and we’re ushered through to our table for the evening. The big reveal of floor-to-ceiling windows across two sides of an expansive open kitchen, revealing chefs framed by sprawling pasture behind them, is fucking irresistible. It’s really beautiful.

There’s nothing more tedious than an invitation to “watch the culinary theatre unfold”. But here, a handful of dining tables are set back just far enough from the kitchen, and there’s a pleasing synergy between farm, process and plate, rather than anything too cloying.

We’re told that, from the other side of the kitchen, cows sometimes wander up to the window and peer in. The sly bastards have well and truly reeled us in here; I genuinely start thinking about the ‘journey’ of the ingredients, and we’ve only eaten a mushroom cookie and some apple so far.

There’s lots of sparse surfaces in the kitchen. Minimal clutter. No pass, no heat lamps, no chef barking instructions, just two sweeping counters and some quiet, busy cooking just out of sight. Plating never happens in orderly rows, formulaically, factory line-style. Instead, there’s an organic, gliding nature to the service, all conducted at a regal, tender pace. Asparagus is caressed. Pork is swaddled. Kombucha is burped. Hell, even the stainless steel seems to be rendered in a more subdued colour palette.

It all contributes to a reframing of chef and diner, kitchen and dining room, into an almost egalitarian exchange. I’m almost ready to leap up and start cooking my own dinner. It’s a tableau you’re happy to be part of, if only for the evening.

Just as it felt like Osip spent a little too long setting the scene, we fear we’ve done the same. So let’s eat.

Wait staff wearing various riffs on monochrome tell us in soothing tones that 85% of the produce used by the restaurant is grown on Merlin’s two biodynamic, organic smallholdings. Service is pleasingly laid back, free from massive speeches seasoning each course as it gets cold, but when prodded, our waiter excitedly reveals the odd secret ingredient. It’s the perfect approach for the energy of the room.

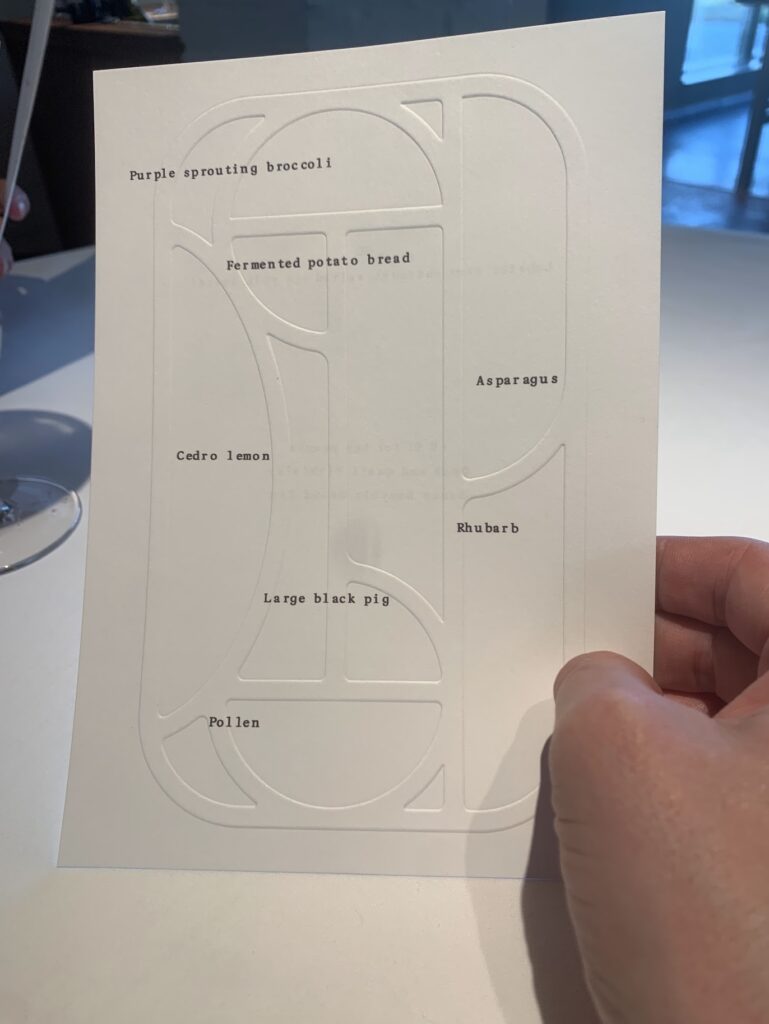

In fitting with the restaurant’s austere leanings, the preview menu’s sparse nomenclature – a list of just six random ingredients —strategically underpromises and overdelivers. Much like the decor and the staff, it lets the food and that mighty kitchen view do the talking.

The tasting menu is £125 (vegetarian too). Lunch is shorter at £95. Wine pairings are £80 for the full menu and £38 (three wines) for lunch—decent value given the standalone bottle prices. The wine list, curated by Andrea Marcon and James Dillon, emphasizes biodynamic producers. It starts at £45, though bottles at this entry point are scarce, with most between £70-£100. A handful are available by glass in the mid-teens.

A more affordable option is Osip’s own cider at £18 for 750ml—enough for the entire meal and to feel celebratory, with smaller bottles available, too. Non-alcoholic options like Botivo and Feragaia are thoughtful alternatives.

The meal proper starts with a lovage broth served to sip cuppa soup style – the first of many decidedly verdant courses. It tastes like a cuppa soup, too. There’s fermented potato brioche next, served with kefir cream and nettles, before what’s billed as a ‘spring taco’. Refreshingly, it is genuinely a taco – the dough made from masa harina that has been spiked with matcha to keep with the verdurous theme, is pressed until its edges fray just right. It’s topped with a piquant, grassy tangle that’s headlined by purple sprouting broccoli.

It’s a perfectly balanced bite, grassy, piquant and just the right side of salty, and the first true indicator that this is a very special kitchen on song and, dare we say, in season. The vibrance, the vitality, after a particularly long winter, suddenly feels poignant.

At this point, the first of several blink-and-you’ll-miss-them power cuts hit the dining room, with the impression that a generator has kicked in to save the day. It felt fitting, perhaps fabricated, hammering home an experience that’s all about its rurality. There’s no Wi-Fi or 5G either – you really are ensconced here.

More delicate, striking courses follow: white asparagus with raw scallop and a bright, remarkable dice of Cedro lemon; grilled mushroom with tiny cubes of fried pig’s ear; lightly smoked trout on fudgy pink fur potato, with a trout roe-studded beurre blanc that had no right being as ethereal as it was.

Sauces are exceptional throughout; the kitchen has a precise, sagacious touch with acidity that undulates all through the tasting menu, peaking and troughing, lightening the load and keeping things interesting.

The finest sauce of the night comes with a supplementary course of lobster, the tail served grilled over charcoal, its bisque arriving separately, seasoned with salted egg yolk, sorrel and lemon thyme. It’s a truly sublime piece of work, complex and intoxicating, but sufficiently aerated to keep things as breezy as everything that preceded it. Its glossy, coral-ochre veneer helps swerve that always unwelcome sense that your siphoned sauce is, in fact, sputum.

The ‘main’ is a one-two punch of pig, the restaurant’s own, which has been butchered down from whole. Firstly, its head, braised, crumbed and deep fried, is served buried under foraged foliage, on top of a perilla leaf that has a spikey, cumin-like kick. Then, a grilled loin and belly, and a gently spiced puck of Toulouse sausage, just a little funky and fermented, comes with nettles and asparagus. It’s a satisfying pay-off, and a fine way to begin realising that you’re getting full.

This palate needs refreshing, and here refreshment comes in the form of a picture-perfect rocher of sorrel sorbet, seemingly levitating above a rhubarb and pistachio oil. It’s cleansing af, this.

Then, the restaurant’s own honey takes a victory lap, in a burnt honey tart whose pastry work is perhaps just a touch too short and whose top is just a little too burnished, but a great dessert nonetheless. It comes with a companion bowl of creme fraiche ice cream, pollen and mead. It’s heady, but surprisingly reviving, too, a useful summation of the meal as we reach its conclusion.

We retire back to the lounge to await our chariot home. With no reception, you can only leave when the restaurant uses its landline to call a cab to come scoop you up. You’re slumped next to the fire, unable to leave as it’s pitch black outside, and you suddenly realise that you’ve run out of things to say, much like this review.

The wait gives you time to enjoy a little Pump Street chocolate and blackcurrant macaron, as well as a carrot and sea buckthorn pate de fruit. The latter leaves a sour taste in the mouth, in the best possible way. Mouth puckered and pert, it’s nice to note that we’re not reeling, neither are we too full to think.

We’re by no means contemplating that kebab on the way home, either. Osip has pulled off a rare thing in a modern tasting menu; a meal that will satisfy you, sure, but also one that will leave you feeling light and invigorated. The evening flew by, it danced along, and didn’t get tiresome or protracted. At times, it verged on the profound.

Anyway, the couple from the start of our meal are back next to us in the holding pen, desperately avoiding meeting our eye as they pontificate on the sprawling but somehow still succinct expression of Somerset seasonality that they’ve just savoured. I realise it’s been me saying these things out loud just as our taxi driver comes through the door, greets Merlin warmly, and then ushers us out.

“I told you, no one ever leaves disappointed”, says the driver Ali as our car winds back toward Bruton. He’s right. It’s clear what Osip has accomplished here; a genuine expression of place that’s so singular, so fully realised, that surrendering to Merlin’s magic feels like the only sensible option.